Overview of Marine Oriented Commercial Record

Ship account books represent just one type of commercial record created by and used by mariners.

Marine Lives volunteers may find it useful to review this Overview of Marine Oriented Commercial Record Keeping.

References to original documents are of two types. References are either foliated or unfoliated. If unfoliated, the relevant deposition book is shown (HCA 13/ followed by the volume number) nd an image number is appended. The image number refers to the digital image made by Marine Lives volunteers.

Contents

- 1 Overview

- 2 Acquittance

- 3 Bill of lading

- 4 Boatswain’s book of accounts

- 5 Book of receipts

- 6 Charter party

- 7 Chief mate’s book

- 8 Cocket

- 9 Custom house book

- 10 Custom house waiter’s book

- 11 Gunner’s inventory

- 12 Letters of advice

- 13 Letter of affreightment

- 14 Letters of correspondence

- 15 Lighter’s book of accounts

- 16 Master’s book of accounts

- 17 Marks on goods

- 18 Miscellaneous papers and writings

- 19 Notes or receipts [supply of goods to ships]

- 20 Notes [wages related]

- 21 Private instructions from freighters or owners

- 22 Protest

- 23 Purser’s book

- 24 Steward’s book

- 25 Waiter’s book

- 26 Warehouse records

- 27 Wharfinger’s book of accounts

Overview

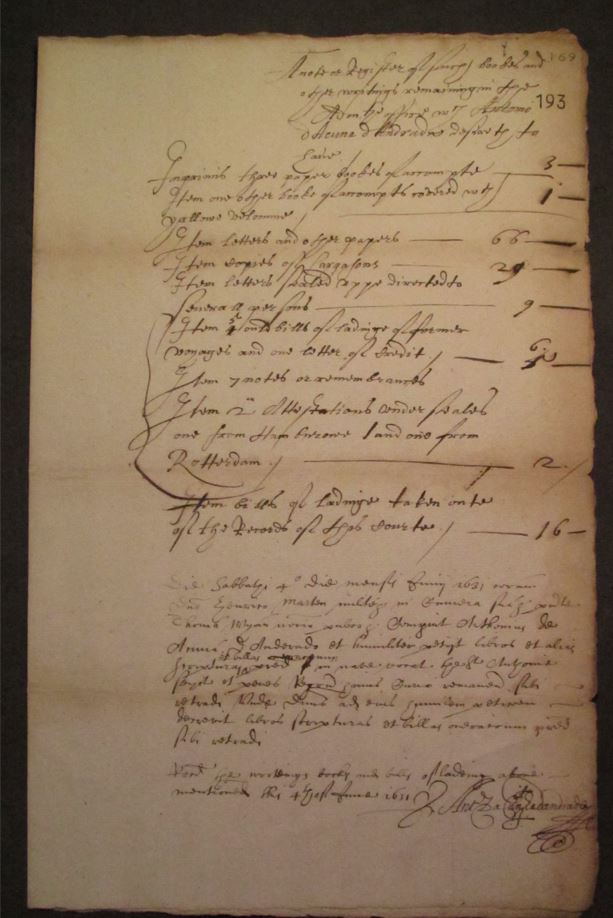

A case before the High Court of Admiralty in 1666 concerning a Flandrian ship, seized by English privateers, illustrates the range of papers on a specific ship.

The ship was the Godliffe, carrying wine from Nantes back to Bruges, when it was seized at the Isle of Wight. It had already been cleared by an English man of war. The master and company were carried to Chichester, where they were examined, their depositions (they claimed) had been written down falsely. They were examined again in London, where they protested their depositions. Documents referred to are a sea brief, a bill of sale for the ship, and an exemplication of the translation of the bill of sale, bills of lading, letters, and other papers.

- "Hee this deponent had a seabrief on board and a bill of sale of his said shipp, together with an exempliflication of the translation thereof, under the seale of this Court, all which together with the bills and other papers the said Captaine tooke from this deponent (who showed them to him for declaration of his clearance) and detained them, and afterwards when hee had brought this deponent to Chichester and there somwhile detained him, this deponent asked of him where his writings aforesaid were, the said Captaine said that hee had sent them to London, and this deponent saying, noe, hee understood that they were in the custody of the hostesse of that house were they were (being the [?XXX ?XXX] the said Captaine produced his said writings and showd them in the presense of Mr Crispe a notary there, and of Captain Wills, and then tooke them againe into his custodie, since which time this deponent hath not seen them, saving his bills of lading and some of his letters and papers hee hath lately seen in the Registrie of this Court but his seabrief, bill of sale and exemplification, together with a discharge from the Captaine of the Breda Frigot (given him having bin aboard her) hee saith are still missing, they being subducted by the said Captaine"[1]

The master of a ship was the key man in terms of the official identity of a ship. A curious case concerning a ship named the Mary Ann illustrates this.

Devon mariner Richard Bayly deposed in 1639 concerning the ship and his responsibilities upon her. He clearly believed he had been hired as her master by a man named William Bushell, who appars to have been a part-owner of the ship. Baylie’s name was the name on the name entered into the London Custom house outwards bound, and it ws his name which appeared on the cocket issued by the London Custom house. Similarly, it required Bayly going ahsore at Gravesend to ensure that the ship ws cleared by the searcher to depart. However, at the Downs, Brown Bushell entered the ship and took command of her. Yet Baylie was unclear whether Brown Bushell exercised that command as Captian or Master.

- "Within the tyme arlate the arlate William Bushell hiered this examinate to serve in the arlate shippe the Mary Ann the voyage arlate to goe alonge with Browne Bushell in that shippe but never tolde him whether hee should be master of her or not, but hee sayeth that entryes were made in the Custome house London before the said shippe went from hence that voyage in the name of this examinate and in the cocketts taken out of the Custome house aforesaid it was expressed that this examinate was master of that shippe, and at Gravesend outwardes bounde that voyage the searchers there woulde not cleere her untill this examinate came ashoare there and shee ws there cleered by this examinate as master of her that voyage, and hee was bound for her gunns, and this examinate was the principall man in her untill shee came into the Downes, and then the sarlate Brown Bushell came aboard her and from that tyme tooke uppon him the full comande of the said shippe, but whether it as as captaine or master of her hee knoweth not".[2]

Acquittance

Acquittances were written by the different suppliers to ships and collected by pursers or ship masters, who then entered them into their books of accompts.

For example, the ropeseller George Margets issued an acquittance for goods supplied to the ship the Merchant Adventure, in which Margets was also a part-owner.

- "As may appeare by the acquittance or receipt given by the arlate George Margets of whom the same was bought and taken up for the said summe which hee doeth acknowledged he thereby to bee in full for all cordage and roaping what soever delivered out for the provisions and use of the said shipp and pinnace which said acquittance is wholley writte and subscribed by the propper hand of the said Margetts and was soe done in this deponents presense."[3]

Richard Court, a joiner, did all the joining work on a large ship built at Deptford named the Aeneas. He received part payment for the work from Sir William Russell and several other men, and gave an acquittance for the largest of the sums received.

- "Hee this examinate beeing by profession a joyner did all the ioyning worcke for the arlate shippe the Aeneas, and founde materialls for the same, and hee sayeth that hee did bestowe all the materialls specified in the schedule annexed to this libell uppon the said worcke, and those materialls and his worckmanshipp aforesaid were esteemed by Goddards ffather and his Majestyes ioyner to bee worth £120 and soe much Goddard aggreed to pay him for the same of which hee received from Sir William Russell £80, from Goddard himselfe £10 and from one Bright £10 and the rest is still due to him, and for the same hee never had any bond, bill or other security, and for the £80 received of Sir William Russell hee gave an acquittance"[4]

Bill of lading

Bills of lading were most frequently signed by the master of a ship. However, if there were a purser on board, the purser might sign the bills, in coordination with the boatswain. But ultimately the master carried the can if the goods signed for were not “free” in terms of their ownership and their customer for that ship to carry. If they could be proven not to be free, they risked being made lawful prize.

In the case of the three hundred ton burthen ship the ffalcon, it was her master, Kendrick Hughes, who signed the bills of lading. He first took the numbers and marks of the goods received into the ship, as recorded in the boatswain’s book, and then signed bills of lading matching the boatswain’s book.

The chief mate of the ffalcon describes this process for us:

- "And this deponent knoweth that the sayd Hughes did signe bills of ladeing for the sayd forty tonnes of wynes at Pembeefe after hee had taken the numbers and markes of them out of the boatswaines booke"[5]

A London merchant, Humphrey Smallwood, gives a detailed description of a master signing a bill of lading for goods he shipped at Barbados into a ship named the Jonathan and Abigail.

- "Hee well knew the allegate Robert Page and was with him aboard the shipp the Jonathan and Abigail this last voyage about 17 dayes before the death of him the said Page which happened in his homeward voyage, and saith that hee this deponent having at the Barbadas shipped the goods in the said schedule mentioned aboard the said shipp and afterwards comming to him the said Page master of her for a bill of lading for the same, the said Page subscribed and gave him the said schedule or bill of lading, which this deponent sawe him the said Page with his owne hand subscribe aboard his said shipp in Carlisle Baye in the Barbadas on or about the 10th of June last, seeing him both supplie the date and write (The parcells received, the condition I knowe not) and then theise words p mee Robt Page with his owne hand in all things as nowe appeareth"[6]

In the case of the purser of the Hannibal on a voyage to Brazil, the boatswain received the goods on board and noted them in his accounts, and then the purser signed the bill of lading associated with those goods, and entered them in his purser’s book.

- "The boatswaine of the said shipp received the goods as aforesaid aboard and first tooke accompt thereof, and by his note this deponent signed the said bills (as hee used to doe for the rest of the lading) and made entrie thereof in his owne book"[7]

The boatswain’s book or account should match that of the purser’s book, or freight book. In the case of the purser of the Good Reason, some goods were laden without bills of lading drawn up and signed, though the purser asserted the verity and accuracy of his book of freight.

- "Hee this deponent was purser of the said ship the Good Reason and according to his office and place did enter into a booke the number and sorts of goods and what pipes, fatts, bales and packes were laden abord the said ship according to his accompt which he had and receaved of the boatswaine of the said ship who as the manner is) doeth usually give receipts and notes for the same, and to what port they were consigned and to whom and did accordingly signe bills of lading for the same except only for the [?foresaid] parcells of goods mentioned and expressed in a schedule annexed to this deponents deposition, for which there were noe bills of ladeing signed by this deponent but doe appeare to be laden abord the said ship by the said boatswaines accompte"[8]

- "The booke [?XXX] and now shewed unto him is as hee beleeveth a true coppye of this deponents originall booke of freight for the said ship the originall whereof was faithfully kept by this deponent and everything was entred thereinto according to the verity and truth of the matter"[9]

Bills of lading documented a contractual relationship between the shipper (the master, or his agents such as purser or boatswain) and the lader of goods on his ship. By signing a bill of lading, with the goods itemised and the port of delivery specified, the master, or his agents, bound the master and ship to deliver the goods well conditioned, the perils of the sea excepted. This is made explicit in a deposition given by an English factor at Lisbon, in a cause concerning salt to be transported from near Lisbon to Galicia. Commenting on the suitability of the master to carry the salt, he notes he did not give any caution, but that the master bound himself and his ship, the Catherine, by bill of lading.

- "He this rendent did passe his word that the sayd Yaxlye should performe safely at Galisia (the perills of the sea excepted) but did not give any caution in that behalfe, but the sayd Yaxly did binde himselfe and the sayd shipp the Catherine by bill of ladinge for performance thereof"[10]

Admiralty court cases frequently includes questions to determine whether witnesses recognised the subscription and hand writing of masters or pursers on bills of lading. Below, a London broker testifies that

- "Hee having seene the arlate Peter de Vinck [master of the Saint James] write his name upon the entry of his goods in the Custome house and at this deponent's house verily beleeveth the subsciption to the schedule arlate being the first schedule to bee of his the said de Vincks ffirm and subscription this deponent remembring the firme and florish to bee the same with this now showed unto him, and the said de Vinck gave this deponent the same bill of ladeing or another very like it of the same subscription for this deponent to enter his wines by"[11]

Plenty of bills of lading were fraudulent, or “colourable” in the euphamism of the Court. The master of the Diamond of Topsham admitted to signing a false bill of lading for broad cloth.

- "Hee signed a bill of lading for broadcloth for the said John Davies of Exeter to be delivered to a ffrenchman in Saint Malos, but it was for the accompt of him the said Davies who went alonge in the shipp and intended to take the same up and dispose thereof himselfe, but put them in a ffrenchmans name to secure them from arresting when they came there"[12]

A Dunkirk born mariner, Peter Butt, had some explaining to do. As sole owner of his ship the Waterhound, he had signed a charter party with French merchants to carry their wines from Rouen to Boulogne. His ship’s company was small, with just two men and a French boy in addition to himself.[13] At Rouen he had firmed a colourable bill of lading for the wines, which bill of lading he had on his ship when seized by an English man of war. The colourable bill, he argued, was to protect the wines from Dunkirkers. He now claimed that a different bill of lading was the real and true bill of lading, which was exhibited into the Court. He himself now lived in Middleburg in Zeeland, with his wife and family.

- "This rendent did alsoe at or neere Roane aforesaid signe one colourable bill of lading for the goods in question to secure the same from the Dunkirkers, which colourable bill of lading hee saith was taken in and aboard his said shipp at the time of the seizure aforesaid and saith and affirmeth as aforesaid that the bill of lading now and in his precedent deposition showne unto him was and is the true and reall bill of lading for the said wynes"[14]

The boatswain of a ship named the ffrogge of Amsterdam unhelpfully contradicted the testimony of several merchants, who were passengers on the same ship. The boatswain stated there were colourable bills of lading on the ship made out for Amsterdam, but that everyone knew on the ship that the goods were to be delivered to Dublin. This directly contradicts the several merchants on board the ship, who tried to explain away bills of lading made out for Dublin, saying that the Hamburg factor on board had power to override those bills of lading and that he intended to deliver the goods to ports and places in either England or Ireland which were friendly to King and Parliament, and that there was no intent to go to Dublin.

- "Before the arlate shipp the ffrogg came from the Matheras this last voyage hee heard the merchant and master of her say that there were bills of lading in her declaring that the goods in her were consigned for Amsterdam, but that those bills of ladeinge were onely colourable and to bee shewen if shee should meete with any of the Parliament shippes in her course for Dublin in Ireland, but in truth those goods were to bee delivered at Dublin and not at Amsterdam and this much was generally then declared to all that shipp's company and they wished all to say that they were bounde for Amsterdam if they should meete with any of the Parlieament shippes. And this examinate knoweth that the reall intention was to have delivered the goods taken in the said shippe at Dublin and not at Amsterdam, if shee had not been intercepted. And this hee affirmeth uppon his oath to bee true, beeing boatswaine of that shippe the said voyage"[15]

The willingness of several members of the ffrogge’s company to testify against the interests of the owners and freighters of the shipp seems to have been encouraged by the offer of her takers to ensure they were paid their wages, and that they would recover their own goods. Thus the ffrogge’s carpenter says

- "Hee hath served and belonged to the interrate shippe the ffrogg the voyage in question 28 monethes and was to have for his wages 28 gilders a moneth but hath not as yet received any part thereof and hee had in her when the interrate shippes tooke her, a pipe of wyne and chest of dryed lemon pills and sayeth that Captaine Younge when hee first tooke the ffrogg asked this examinate to what place shee was bounde and hee said for Dublin in Ireland and thereuppon the said Younge told him that if that were true and hee would iustifye the same uppon his oath, hee should have all his wages paid him and his owne goods restored to him"[16]

Portuguese merchants, fearing seizure by Ostenders or Dunkirkers, frequently inserted the names of free and neutral merchants, particularly those of Hamburg. Francisco Pardini, a London merchant who was a native of Florence, had lived in Lisbon for eight or nine years, and knew the usage there. He stated:

- "Whereas in the bill of lading signed for the goods of the said Gregorie Diaz the name of ffrancisco Dirrickson of Hamborough was and is inserted, hee this deponent well knoweth, that both by the generall practise of Portugueze merchants it is usuall and ordinary to insert in their bills of lading the names of free and neutrall persons as those of Hamborough and others, the better to secure their goods from the Spaniards (with whom the Portuguezes are in enmity) and that in case of a meeting with Ostenders or Dunkerkers, and allso for that this deponent hath had particular and faithfull advise to that purpose from the said Gregorie Diazi"[17]

Another trick was to delay coming aboard a ship when haled and to spend the time manufacturing fraudulent bills of lading. Young English merchant, Harman Goris, protests perhaps too much when it is suggested that they were making new bills of lading when the ship was seized. He denies ever telling the seizors they had been doing this and offers a rather lame explanation as to why he had no bills of lading on board.

- "Hee this deponent did not at any tyme tell the arlate Captaine Saunders that hee had not taken any bills of ladeing at all for his the sayd Goris his goods in the Hare in the ffeild, but saith that hee this deponent told the sayd Saunders only to this effect videlicet that hee the sayd Goris coming in person along with his owne goods (and having before hand sent over land to Cadiz two severall bills of ladeing signed by the arlate John Keene at Roane) intended if neede soe required to have either a noate under the sayd Keenes hand or two bills of ladeing for the two parcells of goods hee had on board her, And by virtue of his oath doth positively averre that hee did not tell the sayd Captaine Saunders that they were taken when they were makeing bills of ladeing or any words to that effect"[18]

Plenty of masters of ships swore blind in seizure cases that their bills of lading were real and not colourable. The master of a ship named the Fortune of Hamburg goes over the top with his protestations. Does he protest too much? He claims he was on a direct voyage from Hhamburg to Madeiras and that all his goods were for Hamburg merchants and for himself, a Hamburg burger and part-owner of the ship. Judge for yourself what you make of his claims regarding his bills of lading:

- "The bill of lading arlate and before mentioned was signed and firmed by him this deponent at Hamburgh a few dayes before his departure with the sayd shippe from thense, and hee affirmeth upon his oath that the same was and is a true and reall bill of lading and no way colourable or fictitious, which hee knoweth to bee true for that hee is the person that firmed the same as master of the shipp in question and shaped her course for Madera in perusance of his ingagement by the sayd bill"[19]

Boatswain’s book of accounts

Boatswains made entries into their boatswain’s book at the time of lading of goods. At the time of discharge at London, boatswains frequently sent notes to the shore in lighters, given to a man from the ship’s company who accompanied the goods in the lighters to see them discharged. These notes would be given to the land waiters who received the goods at a customable key.

Nathanill Green was servant to a mariner, and on a ship named the Patience of London was acting as boatswain’s assistant. He describes the role of the boatswain at the time of discharge of goods from the Patience, and more generally for other ships.

- "Hee hath used to goe to sea in sevrall voyages from this port of London for these five yeares last past and for all that tyme it hath bene a custome in the river of Thames that the masters of shipps when they deliver the merchants goods doe send up one or two of their company in the lighter with the merchants goods to see them landed at some customable key and the boatswayne doth usually send up a note by him or them which goe up in the sayd lighter to the wayter that receiveth the goods on shoare, certifyeinge him which goods are sent up in every such lighter and that he beleiveth that if there be any goods stolne out or imbezelled or receyve any damage unlesse it be by the leakines of the lighter whilest she is fast moored to the sayd shippes side then the master and company of such shipp are (as he thinkcketh) to make good the sayd damage for that as he conceiveth the sayd goods are in the charge of the company of such shipp untill the lighter be gone from the sayd shipp"[20]

Book of receipts

Charter party

Charter parties were typically written on vellum, rather than paper. They were made between the freighters and the owners of a ship. They were signed, sealed and delivered by the parties to the charterparty.

Considerable care was taken in the preparation of a charter party. Often one of the potential freighters took the lead and thrashed out an outline with the master of a ship, who represented the owners in the preparation of the charter party. Once drafted, the charter party would then be perfected, going through one or more iterations, with the assistance of a notary public.

Francis Harrison, a notary public of Saint Stephens Coleman Street, drafted a charter party for a ship named the Safetye. A London merchant named John Tierrye gave the notary instructions in the name of her owners to draw up a charter party for the ship to be let to freight to his brother, James Tierrye, for a voyage into the Mediterranean. The owners subsequently came into the notary’s shop on the back side of the Royal Exchange, and after they had seen a draft, were not in complete agreement.

- "In or about the moneth of September anno domini 1636 last past John Tierrye of London merchant came to this deponents shopp scituate on the backe side of the Royall Exchange London and gavee him directions for the draweinge up of a charter partye for the arlate shipp the Safetye in the name of the arlate Randall Manwaringe and Nathaiel Hawes as owners of the sayd shipp to lett her to fraighte into his brother the arlate James Tierrye for a voyage to be made with her to the Straights for twelve monethes certayne or eighteene monethes at the most at £60 per moneth and after the sayd directions given him the sayd Manwaringe and Hawes or one of them came to him with the sayd John Tierrye to his nowe best remembrance and desired to see a draughte of the charter partye for which the sayd Tierrye had given directions and then this deponent shewed them or one of them the draughte of the sayd charter partye, which they or one of them haveinge perused, disliked in some poynts therof"[21]

London merchant Haniball Allen was one of the freighters of a ship named the Saint Lucar Merchant for a voyage to Cadiz, the Canaries, Lisbon and back to London. He was one of the signators to the charterparty and affixed his seal together with his subscription to the document.

- "Which charterparty hee this deponent knoweth to be true and sawe the same signed sealed by the sayd Samuell Wilson the younger and the rest of the freighters whose names are subscribed thereto, and knoweth the subscription Hanniball Allen at the bottom thereof and the seale under the sayd name affixed to be his his deponents owne hand and seale"[22]

Pursers were usually familiar with the charter party binding their ship.

Richard Poole, who was purser and master's mate of the ship the John and Dorothy of London was privy to the contents and making of the charter party for his ship, which was for a voyage from london to Barbary and Lisbon and to return to London.

- "Which hee knoweth to bee true for that hee this examinate was privy to and knew of the making of the charter partie for the sayd voyage"[23]

The purser of the Gilliflower was familiar with the charter party made between the freighters and the master of his ship, a part-owner, on behalf of all the part-owners.

- "By the charter partie indented and made betweene them and the aforesaid Elias Pilgrim and others the parte owners of the sayd shippe for the sayd voyage which charter partie this examinate hath seene and reade"[24]

Masters sometimes carried colourable charter parties, or no charter parties at all. If surprised at sea, they would choose whether or not to reveal a charter party, according to what they knew or guessed of the nationality of the surprising ship and its possible commission.

The master of the Unicorne of Gottenberg, for whatever reason, chose not to share his charter party at the time of his seizure, but then appears to have mysteriously found it, or obtained a replacement.

- "Hee saith that hee this deponent at the said tyme of the surprizall of the said ship had the charterpartie made for the voyage upon which hee is now bound aboard with him and did not deliver the same with the rest of his papers to the sayd Captaine Lawson but tould him thereof. Which said charter partie this deponent hath now with him and doth leave the same in the Registrie of this Court for the better cleering of the truth in and concerning this business"[25]

English speaking masters resident in London might make charter parties for affreightments in languages other than English.

We have examples of English masters signing charter parties written in French and made up by French notaries. We also have examples of English merchants at ports such as Lisbon signing charterparties written in Portuguese. In an example below, the ship the Hope alias Esperanza may have been a German ship, her master being named Hance Bommelman. Whatever the purported and actual home of the ship, the ship and goods were arrested on arrival at Bristol from Lisbon. A London merchant named Mathew Randolph had to help recover the ship, which his Lisbon based brother had freighted. The Portuguese charter party had been sent to Bristol, and the Bristol consignees sent the original to London, to be translated into English by a London notary and attested to be a true and faithful translation.

- "The said Mr Williams and Mr Pausely sent to this deponent the letter by them received from the said Mr John Randolph to show the said affreightment soe by him made, and the said Charles Williams sent the charterpartie of the said affreightment written in the Portugall tongue to his father in law Mr Beniamin Whetcomb of London merchant, to the end to get it translated into English, and the said Mr Whetcombe accordingly delivered it to this deponents precontest Mr Emmans a notary publique in this citie to be translated as the said Mr Whetcommb told this deponent, to whom hee showed a paper in the Portugall language which hee said was the said originall, and having soe got it translated, hee the said Mr Whetcomb as hee also told this deponent sent the same back to Bristol to the said Mr Williams. And touching the said letters soe received from this deponents said brother Mr John Randulph concerning he said affraightment and premisses hee hath them now with him and is ready to produce them upon any occasion...saving the said Mr Emmans is a legall notary publique and of good imployment and credit"[26]

- "The said schedule is a true translation of the orginal thereof written in the Portugall tongue and in substance agreeth with the said originall, which hee knoweth because hee this deponent made the said translation and then examined it with the originall and found it soe to agree, and finding it to agree with the originall, this deponent a lawfull notary publique and of good credit subscribed his name thereto, which subscription together with the whole translation hee acknowledgeth to be of his owne hand writing"[27]

- "Mr Benjamin Whitcomb of London merchant who delivered the said originall to this deponent to translate, tooke the same back from him againe and said that hee was to send it to Bristoll"[28]

Chief mate’s book

Deptford mariner Henry Marsen was one of the master’s mates of the ffalcon, and describes himself as chief mate. Unusually for a master’s mate, he refers in his deposition to having a book, in which he had recorded types and quantities of goods received into the ship’s hold.

- "Hee saith the ffalcon aforesayd was of the burthen of about three hundred tonnes and upwards, and saith shee brought about a hundred tonne of wyne the voyage in question, beside salt and paper and other goods and saith her hold was full as conveniently it could bee. And saith (for that hee hath not his booke about him and for that it is a yeare and better since) hee cannot answere more particularly as to the quantitie and qualitie of the sayd shipps other ladeing"[29]

Cocket

Cockets were issued by officials of Custom houses at ports when goods were laden on ships to be taken from that port. On arrival at a new port, with goods to be discharged, the master of a ship would lodge his cocket with the Custom house.

In the case of Thomas Andrews, master of the Owen and David, his voyage had been broken due to the empress of his company. He returned into the River Thames and unloaded his goods, including part of his own adventure which he carried on the ship, which was in woollen manufacturies, stuffs and other goods. He could not recall the details and referred the Court to his cockets, which he said remained in the London Custom house.

- “And saith hee had an adventure consisting of woolen manufactory, stuffes, and other goodes, but the perticulers and quantities now remembreth not but saith the same may be knowne by his cockets remaining in the Custome house. Some part of his adventure is yet on board and some on shore"[30]

London merchant John Blunte, deposing in Court in 1609, described the role of cockets in the port of London. In his telling, cockets were issued by the searcher of a ship, and that ships carried these cockets with them as proof that their goods had been customed.

- "Hee knoweth that the use and custome hathe beene time out of minde and at this porte that all masters of shippes doe take from the searcher a cocquette of all suche goodes as they doe carrie in theire shippes, and doe carrie theire cocquettes with them for a testimonie that the goodes in the shippe are customed of this examinate's knowedge whoe hath traded as a merchante theese 25 yeares"[31]

Failure to handle the paper work correctly, or an unsuccessful attempt to dupe the searcher, had real costs in terms of seizure of the unaccustomed goods.

London draper Greg Oldfeild described a particular case in which a cocket was missing and a pack of cloth without cocket seized.

- "He knoweth that the said shipp the Hart comminge to Gravesend was there searched by Mr Tucke the searcher, and findinge that the said Timothy Hart had not a cocquett to shewe for the entring of the said pack with clothes into the Custome house and payeinge the customes for the same seized on the said pack of cloth for his Majesty, and tooke out the said pack of cloth out of the said shipp into his handes by the only faulte and neglecte of the said Timothy Hart who took not out the said cocquett as he ought to have done, and that the said pack of clothe remayned in the searchers hands about three monethes space before the said Robert Oldfield ever hearde it was taken out of the said shippe. And his first intelligence thereof was by letter written him by Mr Blunt from Stade or Hamborough that the said cloth was not brought thither in the said shipp. And then makinge inquiry he found the said pack with cloth was in the searchers hands at Gravesend, and with greate chardges he the said Oldfield recovered the said pack of cloth beinge greatly spoyled and damnified by the longe lyeinge there, in so much that some of the said clothes lyeth in their handes unsould"[32]

Custom house book

It would be naïve to think Custom house entries are always accurate.

Here a London broker elicits a confession from Peter de Vinck master of the James, that de Vinck had disposed of three puncheons of wine in France to pay personal debts. Yet, de Vinck put those three puncheons down in his entry at the London Customs house as being still on his ship.

- "The arlate de Vinck did after the arrivall of this said shipp at London enter his whole lading in the Custome house namely ffifty six puncheons and twenty half puncheons and six hogsheads of wine although hee well knew that three of the said puncheons were wanting and by him disposed of as aforesayd"[33]

John Bredcake, master of the Endeavour of London, was keen to prove that he had made accurate and complete entry of his goods into the London Custom house on departing London for Hamburg. A clerk in the Searchers Office (part of the London Custom house) attested that Bredcake’s copy of his entry matched that in the Searchers Office. Which begs the question as to whether it was accurate in the first place.

- "Uppon the sixteenth day of November last past John Bredcake master of the Endeavor of London did make entrance in his Majestyes Custome house London of all and singular the goods mentioned in the sayd schedule as the true content of all the goods wares and merchandizes laden abord the sayd shipp in her then intended voyage for Hamborowe, and did then make oath before Sir John Wolstenholme knighte collector of his Majestyes Imposts and John Jacobs Esquire Customer, and other officers of his Majestyes Custom house, that the schedule then given in and exhibited by him into the Searchers Office as the true content of all the goods laden abord the sayd shipp the Endeavor in the sayd voyage (as farr as he knewe) and that this deponent also sayes that the sayd schedule exhibited by the sayd Bredcake is subscribed with the proper hand writings of the sayd Sir John Wolstenholme and Mr Jacobs, and that the schedule mentioned in the sayd allegation is a true copie and doth agree in every poynt with the sayd schedule exhibited by the sayd Bredcake before the sayd officers nowe remayninge in the Searchers Office of the Custome house. The premisses he sayeth he knoweth to be true for that he beinge Clarke in the sayd Searchers Office under Thomas Ivatt Esquire, his Majestyes Chief Searcher, did write the sayd schedule exhibited in this Court, and compared it with the sayd originall schedule remayninge in the sayd Searchers Office”[34]

John Berry, a London merchant living in Lombard street in Saint Nicholas Acons, states that his practice was not to use his own name for entries of outbound goods at the London Custom house. Instead he used the name of Thomas Coram, who usually handled Berry’s affairs and biusiness by the way of merchandizing for him as factor in London. He claims the reason for this arrangement was that “he would not have any man to take notice of what goods he traded in, or where he sent them, as is a usuall thinge for merchants heere in London to doe”.

- "In the moneth of ffebruarye Anno Domini 1635 this deponent did cause to be laden abord the shipp called the Abraham of London (wherof James Bartlett was master) one packe marked and numbred as in the margent conteyninge sixtye one peeces of sayes alias perpetuanoes to be transported in the same shipp from this port of London to Rotterdam consigned unto Jacob Garrard of Rotterdam to be by him sent unto this deponent's factor Henry Garrard dwellinge at Amsterdam for the proper accompte of him this deponent, and that this deponent's servant John Burye did by this deponent's order and direction enter them in his Majestyes Custome house London in the name of Thomas Coram who doeth usually doe his affayres and businesses in the way of merchandize for him this deponent as his factor, and that he soe caused them to be entred in the name of the sayd Coram, and not in his owne name because he would not have any man to take notice of what goods he traded in, or where he sent them, as is a usuall thinge for merchants heere in London to doe. And he alsoe sayeth that the sayd Coram is a naturall Englishman borne in Tiverton in the Countye of Devon, and there dwelleth at this present which he knoweth to be true for that the sayd Coram is this deponent's father's sister's sonne. And further sayeth that in the moneth of ffebruarye 1633 aforesayd this deponent did write a letter unto the foresayd Jacob Garrard of the tenor of the schedule annexed unto the articles whereuppon witnesses are examined in this Court on his behalfe, which letter he sayeth doth agree word for word with a letter written amongst others in this deponent's coppye booke of letters, which letter soe written by this deponent he delivered into his servant or some other to be caryed unto the said Bartlett to be with the sayd packe of sayes aforesayd delivered into the sayd Jacob Garrard at Rotterdam"

John Berrys’s servant, twenty year old John Bury, notes the discrepancy between the entry in the cocquet under the name of Thomas Coram, and the entry in his master’s books as the goods he shipped being his own, and attempts to explain this away.

- "Although the name of Thomas Corham be only named in the cockett of the Custome house for the sayd packe of sayes yet the sayd goods as appeareth by the sayd Berry his booke of accompts were for the proper accompte of him the sayd Berrye and the charges of the custome of them was as it likewise appareth by the sayd booke of accompts payd by or for the use of the sayd Berry. And the sayd Berrye hath usually shipt goods which have bene really his owne in the name of the sayd Corham and of other merchants, and that it is a usuall thinge amongst merchants to enter their goods in other mens names"[35]

A London baker went with Captain Robert Clerk to the Custom house at West Chester to search for the entry of two ships in the Custom house books. He recounts how he and Clerk found the entries of the ships the Hare and the Mary in the books, and then had an extract made and certificated under the hands of two principals of the Custom house.

- "Hee this deponent being at Westchester in the somer tyme last past was upon or about the date of the latter of the said two schedules desired by the producent Captaine Robert Clarcke (who at that tyme was there allso and lay in the same inn whree this deponent then allso lodged) to goe downe to the Custome house three, to search for the entrance of two shipps the Hare and the Mary of Dublin, which hee accordingly did, But theire comeing thither they were tould by one of the Officers of the said Custome house that hee could not iust at that instant showe them the Bookes wherein the said ships and theire ladeing were soe entred, but if they would come another tyme hee would satisfie the said producent herein whereupon this deponent and the said Captaine Clarcke departed thence for the tyme, and returned againe, within a day or two afterwards. And then hee saith the said officer in this deponents presence shewed the said Captaine Clarcke the bookes of that Custome house wherein both the said ships and theire ladeing were entred, the one of them videlicet the Hare as comeing from Dublin to Westchester where she was to unlade and the other videlicet the Mary as a ship goeing from thence to Dublin. And thereupon hee saith the said Officer shewed the said Captaine Clercke a certificate of [?that] and the entrance of the said ships and goods abord them in that Custome house, and being perused by Captaine Clerke and in this deponents presence and heareing compared with the said Bookes the said Captaine Clerke desired that hee would procure the same to bee made authentique under the hands and seales of such as were in authority there, which at his request the said officer did accordingly and did in this deponents sight procure the same to bee subscribed and sealed by and with the hands and seals of two of the principall officers there. And saith the latter schedule of the two mentioned in the said allegation is the same certificate which the said Captaine Clerk had from the Customers at Westchester for the entrance of the said ships and goods at that place"[36]

Custom house waiter’s book

Custom house waiters come in two varieties. Those that wait on board ships, typically boarding an incoming ship at Gravesend and staying on board until the ship’s lading is fully discharged, and those that wait on ships on the shore, checking goods as they are landed in lighters and brought to Custom house key for inspection, weighing and taxation. Both ship and shore waiters kept books in which they made entries of the goods they were supervising.

Thomas Markland was a custom house waiter for the excise and grocer, who was assigned to wait on board a ship named the Six Brothers. The ship had arrived in the River Thames from Oporto in Portugal carrying sugar. Markland appears to have made a ship specific account for sugars delivered out of the ship, and then separately entered the sugars in his own book with their respective weights. The sugars were landed at Buttolphs wharf, where Markland stood by the weighing beam and watched the chests of sugar weighed, before entering the weights in his book.

- "Hee this deponent was the Custome house waiter for the excise on the shipp the Six Brothers arlate upon her arivall from Port a Port in Portugall to this port, and tooke an account in writing of the sugars brought hence, and delivered thereout to and for account of the arlate William ffisher, contained in two and twenty chests and two fetches, and of the weight thereof and made entrie thereof in his booke, which hee hath now with him"[37]

- "And saith hee findeth by his said booke and well knoweth that the same upon delivery here at Buttolphs wharfe weighed 203 pounds weight and a quarter and one grosse which quarter and one make twenty nine pounds which hee knoweth because by vertue of his said office hee stood by and saw the weighing of the said two and twenty chests and two fetches of sugar, and entred the same as aforesaid in his booke."[38]

The sugars in question were consigned to William ffisher in London, who gave order for their delivery, acknowledged their receipt and paid the customs due for them. The sugars were delivered in July 1657, and Markland, referring to his book, was able ten months later, in May 1658, to recall the details.

- "And saith the arlate William ffisher was comming to and againe at that time and gave order for sending them hence, and hath since acknowledged the receipt of the said sugars and hath paid the customes thereof, and saith the said delivery was in July last as appeareth alsoe by his said book"[39]

Markland’s training as a grocer is seen in his competent calculation of the equivalency of Portuguese and English weights, he casting up 707 rooves and 25 pounds of sugar in Portugal weights into the equivalent in English measures, which was 202 hundred weight and 25 pounds.

- "That 707 rooves and 25 pounds of sugar Portugall weight at 32 pounds to a roove (which is the usuall computation make 202 hundred weight and 25 pounds as hee hath cast the same up"[40]

At dispute was whether the weight of the sugar delivered out of the Six Brothers matched the weight of the sugar delivered into the ship at Oporto, after allowing for tare or shrinkage. Markland had not seen the original Portuguese invoice, and even if he had, did not speak or read Portuguese. Natural shrinkage of sugar through evaporation or leakage could account for variance between the Oporto weights and the London weights, and Markland provides the Court with some customary allowances for tare of Portugal sugars at London. He goes on to demonstrates that his book entries exactly match the book entries of Mr Webb, a haberdasher, who had been assigned by Mr ffisher to take up the sugars out of the ship. Markland did this by a line item by line item comparison between his and Webb’s books, comparing mark, number and weight of each chest of sugar in his book with the same information in Mr Webb’s book.

Gunner’s inventory

Specialists on C17th merchant ships maintained their own stores and kept records in the form of written inventories, This was true of carpenbters, coopers, gunners, and probaby cooks.

The cook’s mate of the Love states the ship’s gunner drew up an inventory of the ship’s gun room stores before the ship was handed over for use as a ship of the English Parliament.

- "To his remembrance the gunner of the said shipp gave an inventary of her store to Captaine Miller commannder of her about a day or two before shee was delivered up to the Earle of Warwicke as aforesaid the said gunner then leaving her"[41]

Letters of advice

The term “letters of advice” appears frequently in depositions by London and other merchants in the English High Court of Admiralty. It is used to encompass XXXX.

Letter of affreightment

A simple alternative to the draughting and signature of a charter party was to prepare and sign a letter of affreightment

In this example, Thomas Sharpe of Newcastle let the ship the Thomas Bonadventure to freight to John Johnson of Randerhouse. Daniell Wilkinson was to go master of the ship. Wilkinson was to sail the ship at the first opportunity from the port of Tiinmouth (near Newcastle) to Amsterdam, where he ws to deliver a lading of coals to John Johnson, his factor or assignes. a period of fourteen days was set in which the discharge of the lading was to take place. The freight was set at two thousand gilders (approximately two hundred pounds sterling), together with the cost of lighterage and other small sundry charges. The letter of affreightment was dated at Sheilds,, the 17th of February 1643/44 and was signed by Thomas Sharpe and John Johnson. In contrast to a charter party, the letter was neither witnessd, nor notarised, and there are no seals affixed to the letter

Letters of correspondence

Edward Barton was Barbados agent in the years 1655 and 1656 to the four owners of a ship named the ffreindshipp. Barton refers in his deposition to having letters of correspondence with the ship’s owners, rather than letters of advice.

- "Hee this deponent was in the yeares 1655 and 1656 arlate agent at the Barbados for the arlate Isaack Barton and one Mr Samuell Pixley and Richard Pixly and Captaine John Mills who were then owners of the arlate shipp the ffreindshipp, which shipp was by them as owners consigned to this deponent as their agent at the Barbados and was (as by letters of correspondence sent from them to this deponent hee was given to understand fitted and furnished for the voyage in question videlicet for a voyage to be made with her from London to the Bite in Guinney, and thence to proceed with negroes to the Barbados and thence to be dispatched by this deponent for London"[42]

Lighter’s book of accounts

[ADD DATA]

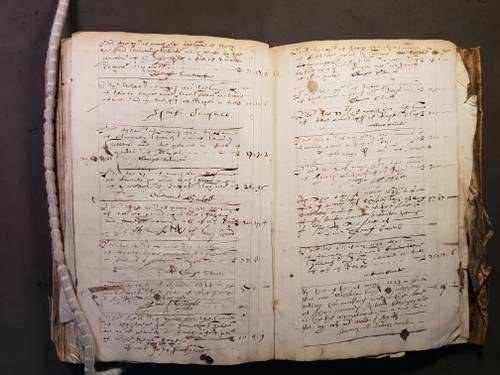

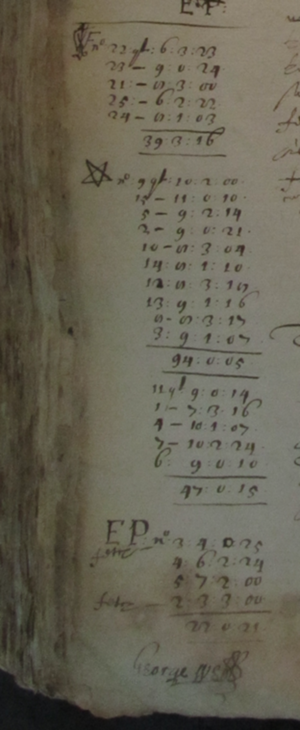

Master’s book of accounts

Master of the Olive Branch

James Jackson the younger was master of the ship the Olive Branch. His book of accounts was brought into the English High Court of Admiralty by Mr Budd, one of the proctors, and shown to a witness, an Ipswich mariner. The witness states that most of the book is written with the hand of James Jackson the younger, and that he the witness was present on November 21st 1657, when Jackson met with the ship’s owners to make up, agree and sign the accounts. The Ipswich mariner, John Rudd, was one of two witnesses to the agreement and signing of the accounts, and added his signature to the accounts

- "Hee well knoweth the booke of accounts now exhibited and brought in by Mr Budd to be the booke of accounts of and concerning the ship the Olive Branch whereof James Jackson the younger was but now James Jackson the elder is master and most part of the said booke is as hee verily beleeveth written by and with the proper hand writing of the said James Jackson the yonger this rendent being well acquainted with his had writing having often seene him write, and saith that on the 21th of November 1657 or neere thereabouts the account touching the said ship was made up betweene the owners and the said James Jackson the yonger, hee thsi deponent and Mr William Wood whose name is with this deponents subscribed to the said account were present thereat. And saith that the said ship then had to this deponents best remembrance as hee beleeveth one hundred and thirty pounds in stock as is sett downe and expressed in the said Booke of Accounts"[43]

Master of the Mayflower of London

Thomas Bell, master of the Mayflower of London, describes receiving goods into his ship at Lisbon from an English factor thence, to be transported to Brazil. The bills of lading for the goods were signed by his purser, but Bell himself entered the goods into his book of accounts.

- "To the first and second articles of the said alleagtion and to the second schedule thereunto annexed hee saith and deposeth that in the moneth of May last [1649] or thereabouts there were laden and put aboard the shipp the Mayflower aforesaid at Lisbone all the goods wares and merchandizes schedulated, marked and numbred as in the said schedule by Robert Carr, an English factor there resident to be carried and transported in the said shipp for Brazile and there delivered which hee knoweth because hee this deponent was then commannder of the said shipp and received the said goods aboard and entred the same in his booke which hee hath nowe seene, and saith hee beleeveth the same were laden for the accompt of the producent Barnabie Crofford, because hee hath nowe seene the bill of lading for the same, subscribed by his this deponents purser mentioning the ladingthereof for the accompt of the said Crofford, and consigned to Deiego George da Silva at Bahia in Brazile"[44]

Captain of the London

Five years after receiving supplies from a rope merchant, the commander of the ship the London, Captain John Stephens, was able to identify the exact book entry for the good supplied, with quantities and prices, citing the specific folio in his book of accounts.

- "To the said allegation and the first side of the 402 leafe of the said booke hee saith and deposeth that hee this deponent being commander of the said shipp the London did by his purser and boatswaine in the yeares 1649 and 1650 receive aboard her of and from the producent Mr David Davidson rope-merchant the severall and respective materialls and goods mentioned and expressed in the said first side of the said 402 leafe, at the prices there alsoe set downe, (which then were the usuall and ordinary prices of such commodities) amounting in the whole to £74 – 15 s – 9 3/4 d, which said goods and materialls hee saith were used, spent and imployed in and about the said shipp, all which hee knoweth being commander of her as aforesaid and giving order to the said Davison for the deliverie thereof to her use, and being afterwards made acquainted by his purser and boatswaine with the receipt thereof aboard"[45]

Servant to master of Great Saphire

John Hosier, twenty-two year old servant to the master of the ship the Great Saphire, had frequent access to his master’s accounts during his master’s lifetime. After the death of his master (at the time of the casting away of the ship in the Mediterranean), Hosier could recall many of the employment details of the ship’s company, including the date certain men left the ship at Livorno, and the wages of the chirurgeon, the chirurgeon’s mate, the master’s mate and the cook.

- "All and singular the persons mentioned in the sayd first schedule served in the sayd shipp all the voyage arlate untill she was cast away (excepte Richard Stone and David Evans, who left the sayd shipp at Leghorne the nyneth day of December last past, and the sayd shipp ws cast away the 11th day of the same moneth. And hee further sayeth that William Plumsteed the chirurgeon of the sayd shipp and Thomas Content his mate (as appeareth by the accompte kepte of the sayd Thomas Meade deceased in his life tyme of the names of his company and their wages for the voyage arlate which this deponent hath often seee in the sayd voyage and well remembreth) were to have for them both foure pounds per moneth William Pitman the masters mate of the said shipp was to have thirtye shillings per moneth, John ffoxe the cooke was to have 24 shillings per moneth, but what the rest of the partyes schedulated were to have per moneth he remembreth not"'[46]'

Without their books, or books of account, or books of memorandums, as they are variously described in HCA 13 series depositions, masters of ships often felt bereft of information.

Master of the Happy Deliverance

- "Hee having not now about him his booke of memorandums cannot more perticulerly answere to this interrogatorie than in his foregoeing deposition is declared" [47]

Boatswain of the Anne

- "The bookes of accounts belonging to the ship, was not brought out, but left in her, when her company left her. And saith that, after the said ship struck upon the sands, her company had noe time to take any of their owne goods (save what they had about them) but were all busied about hoysting out their boate"[48]

Master of the Jonathan and Abigall

- "The acknowledgement and confessions that this deponent hath made touching the lading of the said goods on board the said ship were made before hee had perused his booke wherein he tooke note of such things"[49]

Master of the Companyon

- "His this respondent's wages for his service in the said ship Compagnon were to about fifty pounds some of which hee hath receaved from the said owners or their order upon [?documents] but how much hee cannot without booke declare and his is suddenly to even all accounts with them and saith that some money hee hath receaved of the said owners or by their orders since this suite began relating to the said ship and her busines"[50]

It was often expedient at times of unrest (namely most of the time in the first half of the C17th) not to enter all goods into the master’s books, or to make colourable entries.

Master of the Winefat

- "Hee can write and reade and had a booke at [?XXX] and the name of the merchants to whom consigned entred therein, but [?not] his lading entred, it not being found expedient in theise times and troubles at sea to make entrie thereof, or therfrom whom received and to whom to be delivered"[51]

Master of the Crosse of Jerusalem

The master of an Amsterdam ship the Crosse of Jerusalem was indignant that his seizors had attempted to alter his books, so that it appeared there were two not six bales of linnen laden on his ship. He deposed that someone had attempted to scrape away part of a clear figure six in his book to alter it into the figure of a two.

- "The said shipp to be transported thence to Cadiz or Saint Lucar in Spayne, and that of his certaine knowledge the said six bales of linnen were laden and stowed in the hould of the said shipp, and with in the hould in a good condition and not betweene the decks at the time the said shipp and her lading were seized on, And he further deposeth that he being master of the shipp arlate for the voyage wherin she was taken did upon the lading of the said six bales of linnen aboard the said shipp enter the same accordingly into his owne booke, and made a very faire and plaine figure of sixe in the entring therof which booke some of the shipps company who tooke the Crosse of Jerusalem did take from him the deponent, and that they or some of them have endeavoured by scraping or razing the figure of 6 made by him this deponent to alter the same into the figure of two, as by the said booke (which he doth at this his time of examination diligently peruse) doth appeare"[52]

Masters had a wide range of papers in their possession on their ships during a voyage. The Master of the Thomas and Peter kept details of the wages of his company in a pocket book, separate from his book of accounts.

Master of the Thomas and Peter

- "He had on board a booke of accounts and a pocket booke concerning wages and other things relateing to ships use which are in his chest at Portsmouth and also a passe for the said shipe from the late King James at the time of her seizure onboard which said passe he doth leave in the Registry of this Court and saith that there were not any other papers or writings concerning the said ship or her ladeing then onboard"[53]

The master of the Great Alexander

The master of the Great Alexander died on a return voyage from Brazil to Lisbon. His chief mate took into his possession all the master’s wearing clothes, papers and writings, including a Commission from the King of Portugal. The papers were delivered to one of the owners of the ship on its eventual return to London.

- "The said Garland dying in the said ship Alexander her returne from the Brazil the said voyage, all his wearing cloathes, papers and writings came to this deponent's hands, amongst which papers and writings this deponent found a paper written in the Portugueze language and a seale thereunto which hee verily beleeveth was the said paper soe shewed to him and the rest of the Alexander's company and likewise beleiveth that it was a Commission from the King of Portugall to take his Enemyes, but the effect thereof hee knoweth not in regard hee doth not well understand the Portugall language, but saith that hee sawe that the said Garland was put in and named as Captaine, which paper this deponent after the said ship's arrivall here amongst other papers delivered to Mr Alexander Bence junior of London merchant"[54]

Masters often worked with accountants on shore to whip their accounts into shape before submission for approval and signature by all their owners.

Practioner of Mathematics

- "Which hee saith hee knoweth to be true because hee this deponent for all the said time and before kept the booke of accompts for the said shipps setting out and retourne for severall voyages and therein hath set downe the name and names of the respective owners and their parts and shares of the shipp, and particularly that the said Margets and company were owners of fifteene sixteenth parts of the [?XXX], and the said Richard Hampden (whom this deponent knoweth by sight) owner of the other sixteenth part"[55]

Commander of the Saint Lucar

- “The particular summe [?or] the share of the said Hampden hee knoweth not without booke but therein refereth himselfe to the said booke of accounts, which is in the custody of the said Morecock, who made it up and was booke keeper in that behalfe”[56]

Master of the Sarah Bonadventure

The master of the Sarah Bonadventure, Juniper Plover, made multiple voyages from London to Newastle to fetch coal in 1648. He produced accounts for these voyages in the form of a book of accounts, which he signed, together with the owner of the ship, Mr Barker, who also signed the accounts. The account signing took place in XX at Mr Barker’s house.

- “By the booke of accompts kept for the voyage or voyages in question by the sayd Juniper Plover, hee the said Plover doth make the said shipp the Sarah Bonadventure and the owners of her deliverers for goods wares and merchandizes monies and provisions taken up for the iuse of the said shipp the summe of £295-3 shillings-1 pence, as by his booke of accompts appeareth, and saith that the schedule hereunto annexed was and is a true copieor abstract of the said Juniper Plovers accompts touching the premisses (the booke whereof is in the custody of the said William Barker) and was and is extracted or copied out of the said booke by this deponents hand and doth agree therewith. And saith the said originall booke was and is subscribed with the proper hands of the said Plover and of the said Mr Barker, which hee knoweth because hee this deponent was about six or seaven monethes since present in the said Mr Barkers house in Greate Saint Hellens together with his contest John Whales and did see there the said Mr Barker and Plover subscribe the said booke as nowe is to be seene and thereupon the said Mr John Whaley and this deponent set their names thereunto…”[57]

Common man of the Diamond [LITERATE]

- “This deponent was shipped at £1 – 8 shillings null pence and received of the said Mr Noble [the master of the Diamond] £9-2 shillings-0 pence accordinge as is charged in the said booke of accompts and others of the said ships company were of this deponent’s knowledge paid by the said Noble according as is sett downe in the said booke of accompts”[58]

Master’s books were important records, and were kept for years after specific voyages were completed.

Wife of John Cock, former commander of the Laurell Tree

We learn from the examination of Martha Cock, wife of mariner John Cock, that she searched her husband’s book in his absence, for details of the service of an Anthony Couch, who had sailed on her husband’s ship the Laurell Tree. The book she searched may have been a combined book of accounts, wage book and journal, since she identified the date of Anthony Couch entering into service, and found details of the actual voyage and the insufficiency of the proffered cargo at Barbados. The year of her examination was 1684, but the records she accessed were from 1673/74, ten years earlier.

- "She is aged near forty and wife of John Cock of Wapping Wall near London formerly commander of the ship Laurell Tree…This deponent's husband beinge now absent at Carolina shee this deponent thereto requested by the wife of the said Anthony Couch did search in her said husband's book and did there find that Anthony Couch entred himselfe in the service of the said shipp Laurell Tree upon the fourteenth day of March 1673 English style in a voyage shee was then about to make from here to the Maderas and so to Barbadoes at which two places shee arrived but at the last place not meeting with a cargoe according to expectation shee proceeded and came to Jamaica and to home. And shee sayth that by the said book shee finds that the said Anthony Couch was discharged upon or about the seaventh of March following 1674 same style"[59]

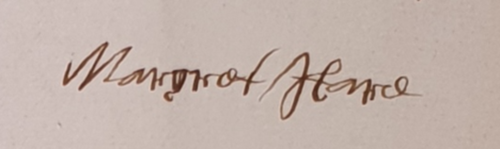

Margaret Hare, wife of late commander of the John and Mary

Margaret Hare, the widow of another mariner, who has been commander of the John and Mary, searched her deceased husband’s records, at the request of the wife of Anthony Couch, who had made a similar request to Martha Cock as above. The year of her examination was 1684, but the journal she found and read covered 1672 and 1673, twelve years earlier.

- "This deponent being the widdow of Josias Hare, late comander of the ship John and Mary about nine yeares since deceased did at the request of the wife of Anthony Couch (a prisoner as is sayd in Lisbon) search in her said deceased husband's journall to see what time the said Anthony Couch entred aboard and when discharged. And shee sayth that in the journall for a voyage to the Canaryes shee did find that Anthony Couch did enter into the service of the said shipp in the middle of 1672 and was discharged therefrom in May following 1673"[60]

Masters were loath to share their books of accounts if they were seized, since they made explicit the laders and customers of their goods.

We learn from the master of the Oxford Frigate, in his Majesty’s service, that the master of the Saint John concealed his book of accounts. The book was discovered at the time of his examination when the master was searched and forced to open up his garments, revealing the book against his breast.

- "The 24th of August 1667, this deponent in the Oxford frigot in his Majesties service having taken the shipp Saint John arlate John Williamson late master, the said master delivered up unto this deponent at sea severall papers and writings as being his shipps papers, and afferred that they were all the papers and writings which hee had had that concerned the said shipp and goods, And saith that this deponent and company bringing up the said shipp Saint John and lading to Kingston upon Hull (where hee put them into the custody of the Commissioners for Prizes), the said master was there examined before the said Commissioners about tenn or twelve dayes after such seizure, and this deponent hinting to the said Commissioners that he had felt something hard upon the said masters breast, and that hee suspected hee had there some papers or writings concealed, Mr Johnson and this deponent took the said master aside into a roome, and causing him to open his garments upon his breast they ther founde his booke, being (as hee by the fashion and size thereof conveiveth) the very same nor showed unto him, and the said master then confessed that it was his shipps booke, and this deponent charging him with the concealement thereof, and asking him why hee had dealt soe untruely with him in saying that hee (upon delivery of the former papers) had noe other, hee blushed and looked very [?sadly] and said hee ws loath to have that book seene, it containing his accompts"[61]

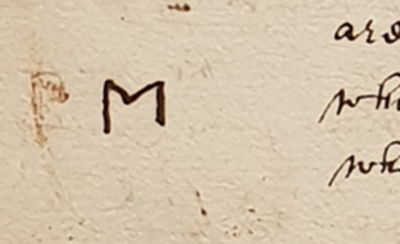

Marks on goods

Even the simplest of commodities carried a mark, whether on a cask, or a box, or on a tag attached to a frail of fruit or a roll of tobacco or a sack of pepper.

When two London fruiterers lost a lading of apples on a Milton hoy heading up river to London, a third fruiterer went into the Admiralty Court to claim some of the fruit on behalf of his friends. He had seen eighteen maund of the missing apples in the custody of a Barking fisherman, and recognised them by the mark of an “M” in red ochre, which was the usual mark of the two fruiters, John Williams and Morrice Weaver.

- "As hee hath heard uppon Tuesday last aboute tenn a clocke the same day aboute twenty miles belowe Gravesend in the River of Thames a small hoy of Milton belonging to one Carter of Milton being laden at Hasted in Kent with thirty maunds of apples by one Morrice Williams to bee broughte in the said hoy to this porte of London for the use and accounte of him the said Williams, and one John Weaver both ffruiterers of London, was over sett, by which meanes the said maundes of apples were lost eighteene maundes of which apples soe loste as aforesaid hee this examinate hath since seene at Barckinge in the possession and custody of one Vaughan a ffisherman, and two more of the said maundes hee hath alsoe seene in a mans yarde at Barckinge but his name hee knoweth not, and hee well knoweth that the said 18 maundes of apples in the custody of the said Vaughan and the other twoe maundes did and doe properly belonge and appertaine unto them the said Morrice Williams and John Weaver for that the said maundes are marked with the marke in the margent with redd oaker which is the usuall marke of them the said Williams and Weaver whereby they marke all theire fruite"[62]

Miscellaneous papers and writings

The master of the Armes of Danzig admitted under examination to having had an old pocket book on board his ship, containing some old bills and acquitances and other things of no consequence concerning his ship. These he threw overboard, as four French men of war approached his vessel.

- "He had on board a pocket booke relateing to former voyages wherein were some old bills acquaittances and such like things of no consequence nor any manner of wayes concerning the said shipp which said booke and bills in it the rendent threw over board when four French men of war comeing aboard him just after he had put to sea for fear they might cause him to be seized but that there were not any other papers or writings whatsoever either torne burnt throwne over board concealed or otherwise embezilled"[63]

When the ship the Mary Jane, allegedly of Jersey, was seized by the Hopefull Luke, the Mary Jane’s master claimed all his papers had previously been seized by a pirate at sea. This, he asserted, was the reason he carried no charter party, coquetts, bills of lading, or instructions from his owner.

- "At the tyme of the seizure of the said shipp the Mary and Jane hee this deponent had noe instructions, charterpartie, cockquetts bills of ladeing no any other writeing whatsoever. All his papers which he brought from Saint-Mallo with him for the said voyage being taken from him before hee arrived at Newfoundland by a pirat which hee met at sea, neither were there any ppaers or other writings whatsoever throwne over bord or otherwise concealed"[64]

A highly experienced thirty year old mariner was living in Cornwall, but serving as pilot and mate in a Dutch man of war named the Overijssell of Amsterdam. He was asked by the master of his ship to peruse the entire range of papers taken from a ship named the Osanna (which itself had been seized by a ship named the Saint Michael of Sweden). Having done so, he determined that the Osanna, together with her lading, belonged entirely to Dutch men, who were subjects of the United Provinces.

- "He saw the ship Osanna lying under the ffort aforesayd and well knoweth that she was and is a Dutch built ship, and sayth that all or most of her papers being taken in the Saint Michael and brought aboard the Overissell this deponent was ordered by Captaine Enna Douda Star to peruse them, and sayth that by them he found that the ship and lading did wholly belong to Ducth men and subiects of the States of the United Provinces"[65]

Notes or receipts [supply of goods to ships]

The shore trades supplying ships moored in the River Thames generated plenty of paper.

Goods were entered into shop books.

Debts were recorded in debt books.

Incoming and outgoing cash was recorded in day books or cash books.

Bulk goods such as iron work and wood were often delivered against a tally stick.

For all goods supplied to ships, notes would be given from the recipient, often under the hand of the master of the ship receiving the goods, but sometimes the purser, should there be one. Acquittances would be issued, under the hand of the master of the shop, yard, or smithy which had delivered the goods and received payment thereof.

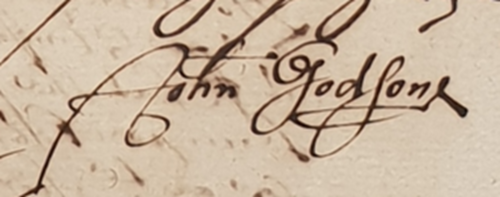

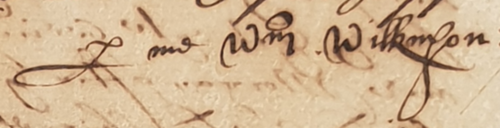

Receipt for beer and matching book entry at brewers

John Goodson, a literate house clerk to a Southwark brewer, was confident of the quantities and prices of the beer delivered from Mr Morgan’s brew house, because of the note he had received under the hand of the master of the Plaine Joane, for whose ship the beer was delivered.

- "And this hee saieth hee knoweth to bee true because hee saieth this examinate beeing then houseclarcke to the said Mr Morgan, after the said beere was soe delivered aboard the sayd shippe, did goe to the said Traves, and had a noate from him under his hande wherby hee did acknowledge that soe much beere was delivered by the said Morgan aboard the said shippe the Plane Joane (sic), and in that noate soe subscribed by the said Traves the said beere was rated and prized at the respective rates and values mentioned in the said first schedule"[66]

A second man, William Wilkinson, describing himself as brewers clerk, set down the prices and rates contained on the receipt for the goods in the house book. His subscription, as does Godson’s, suggest a good degree of written proficiency.

- "This examinate by the direction of the said Morgan who told him that Mr Traves did agree with him the said Morgan for the said beere at the severall rates and prizes mentioned in the said second schedule did sett the said beere downe in the house booke amd did prize and rate it at the said severall rates and prizes mentioned in the said second schedule...The boatswaine and others of the companie of the said shippe did receive the said beere from this examinate aboard the said shippe the Plaine Joane"[67]

An interesting deposition by Philip Griffen, a merchant of Saint Magnus, London, refers to notes under the hands of mariners to be provided to their wives, which the wives could then submit to the ship owners to get one or two months pay in advance of their husbands return to London.

Griffen had been at the ffleece tavern in Cornhill at the hiring of a number of mariners for a voyage from London to Guinea and Barbados, then back to London, in a ship named the ffreindshipp.

- "One or two moneths pay should be paid to their wives in their absense or that their wives brought a noate under their hand to the owners of the sayd shipp for the same. And the sayd Towers and the sayd other mariners then hyred did consent to such agreement to receive their wages at London at the end of the sayd voyage, their sayd wives having a month or two moneths pay paid them in their absense, and this agreement hee saith was soe made in the yeare 1655 at the place aforesayd in the presense of this deponent and the sayd Barton Wills and Pixley and about a moneth before the departure of the sayd shipp upon the sayd voyage"[68]

Private instructions from freighters or owners

In the Early Modern marine world not everything is what it seems. Bills of lading and charter parties may be colourable. And there may be multiple versions of these same documents, one real and one colourable, with the colourable documents on the ship and the real documents sent by land

This is what lies behind the answer by Joseph Hall, master of the Thomas and Peter, to a question to about the existence of private instructions. His ship was seized en route from Haver de Grace to Toulon and carried to Portsmouth.

- "He signed 3 bills of lading for the 400 barrills of tan aforesaid which were sent away to Tholon by land that he had no private instruction concerneing the said ship or her ladeing but was to saile directly for Thoulon and there deliver the said 400 barrills of tan and receive his freight which was to be 2 dollars per barrill and his port charges"[69]

Protest

A protest was a formal legal act involving a written, signed, sometime notarised document. It was made in the event of one party to a contract perceiving that the contract was not being upheld.

Factors might protest against the master of a ship (and his ship) for failing to accept goods he was contracted to do under a signed charter party, or for failing to adhere to other conditions within that same charter party.

Masters of ships might protest against what they consdered to be unreasonable demands by factors, or for the factors’ failure to deliver the contracted quality and amount of goods within the contracted time.

Mariners might protest against the master of their ship should he make demands on their employment which they consider unreasonable, such as extending the length of a voyage beyond the time the mariners contracted for, or changing the voyage to take in a different, more dangerous geography (such as Brazil, the Barbary coast, and the East Mediterranean).

A protest wasn’t worth the paper it was written on if the belligerent party insisted on their actions. It was only of use later should a dispute reach a law court.

Robert Grove, a London merchant, of All Hallows Staining, remembered a dispute between him as factor on a Dutch owned and Dutch crewed ship the Whalefish of Amsterdam. The ship was chartered to sail to the Canaries and to return to London with a lading of wines. Yet, for reasons Grove does not explain with any credibility, the master and company refused to do so. Grove made a defiant protest, witnessed by two English passengers. At which point the master took down his sword from above his head in his cabin and threatned to kill Grove. The ship sailed on to Amsterdam.

- "They expresly refused and sayd that they would goe to Amsterdam to their wyves and children, and that many of thei countrymen had bene abused and could have noe justice in England, and therefore they would carry the sayd shipp and goods into their owne countrey, where they were sure to have justice. Whereuppon this examinate before two English men passengers then in the sayd shipp made a protest against the sayd master and company for breach of charter party in not carryinge the sayd shipp and goods to Londonand then the master of the sayd shipp tooke down his sword hanging over his head in the cabon and thretned to kill this deponent for makinge the sayd protest"[70]

In a reverse example of the above protest, the master and company of a ship named the Jonathan of Bristol refused to sail for Middleburg in Zeeland to deliver a lading of tobaccoes taken on at Saint Christophers. The merchant on the ship, Thomas Browne, drew up a protest against the master and company, and requested that they sign the note. They refused to sign, but acontinued to refuse to sail from the English coast to Zeeland. Instead, the master, and most of her company, carried the ship and her lading to Bristol.